The world is on the cusp of an energy transformation, in which Australia is poised to become a renewable energy superpower, thanks in large part to the potential of renewable energy sources in its vast maritime zones—and in particular, offshore wind.

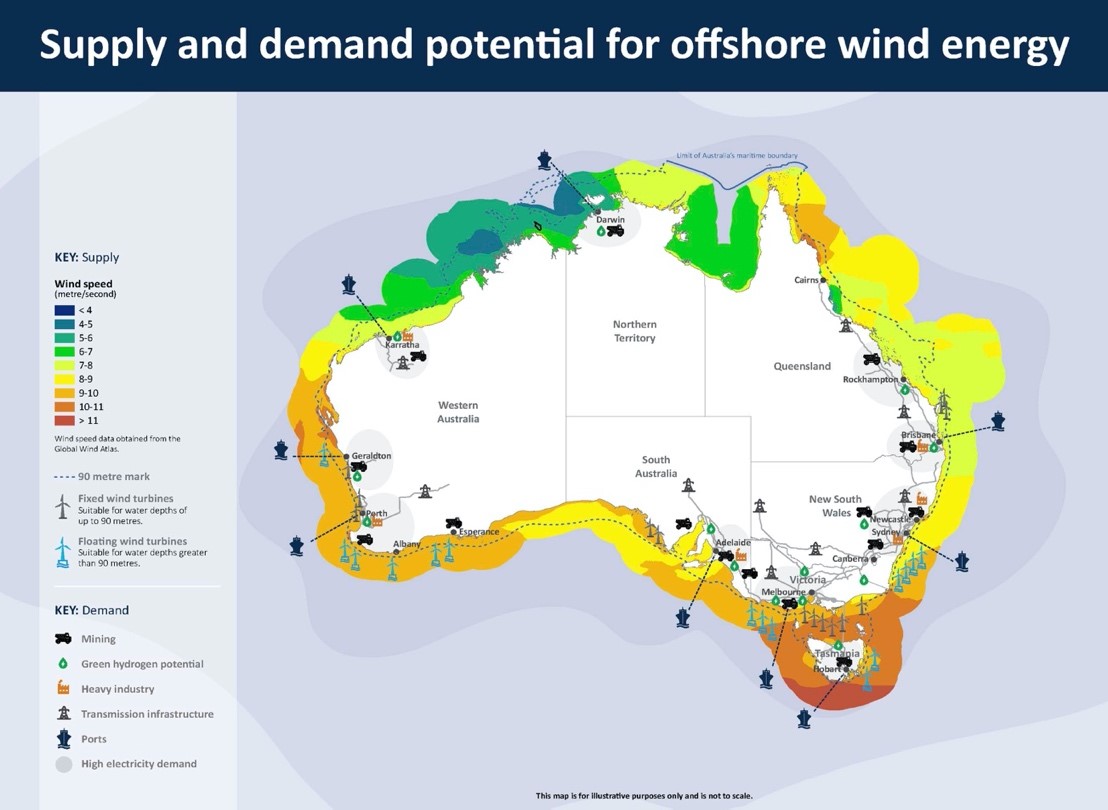

In a 2021 report, the Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre estimated that exploiting the ‘technically accessible’ portion of Australia’s offshore wind resources—using only areas which are less than 100 kilometres from land, less than 1000 metres deep, within 100 kilometres of existing electricity transmission infrastructure, and not subject to environmental restrictions—could generate 9,396 terawatt hours (twh) of electricity per year. This would far exceed Australia’s needs: for example, the existing National Electricity Market only generates about 204 twh of electricity annually, across all energy sources.

What does offshore wind look like in practice?

An offshore wind farm consists of fixed or floating wind turbines that generate electricity, which is then transmitted via undersea cables, through offshore sub-stations, to on-shore infrastructure where it enters the electricity grid.

Accordingly, the best locations for offshore wind have high and consistent wind speeds, appropriate water depths, and are located close to existing electricity transmission infrastructure, or in an area where energy is required to support industry (such as mining or steel and iron ore production, or the production of other energy products such as green hydrogen). Australia has a number of locations which meet this description, and their potential has not been lost on developers, with more than 20 offshore wind projects already at different stages of development, and construction planned to commence as early as 2024.

Image: NOPSEMA

How is offshore wind regulated in Australia?

Until recently, the exploitation of Australia’s vast offshore wind resources was hampered by the absence of any relevant domestic legislation. This changed in June 2022 with the commencement of the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021(Cth) (‘OEI Act’), which provides a regulatory framework for the development and operation of energy infrastructure in Australia’s waters.

Since the exploitation of offshore wind involves activities at sea, it is also important to consider two other legal frameworks that apply in Australia’s waters:

- international law, and in particular the rights and duties of coastal States and other States in the maritime zones established in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea(‘LOSC’),and

- Australia’s domestic Offshore Constitutional Settlement (‘OCS’) arrangements, which divide responsibilities in Australia’s waters between the Commonwealth and the states and territories.

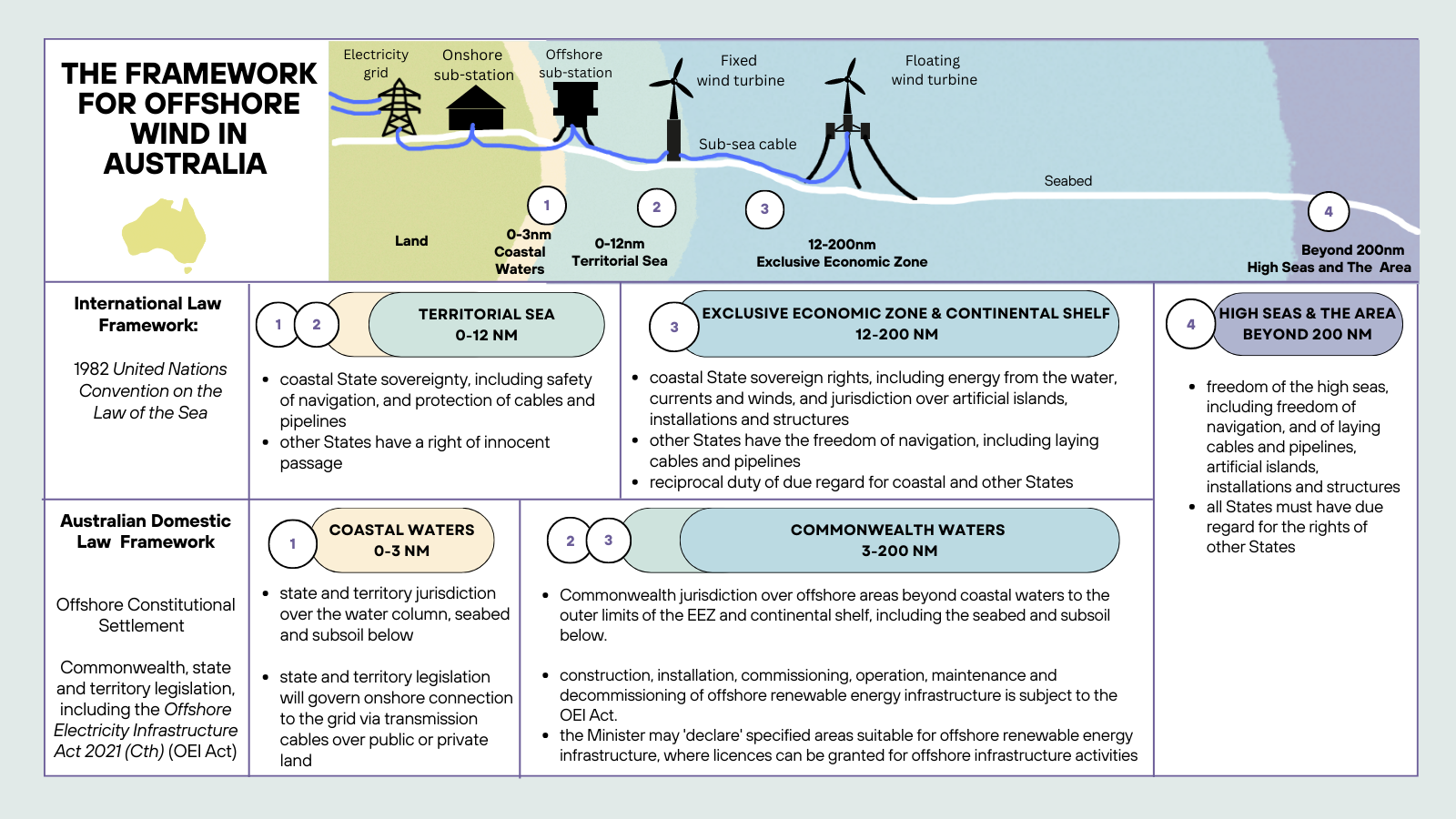

Image: Author

As illustrated here, both the LOSC and the OCS adopt a ‘zonal’ framework for Australia’s offshore area, under which different rights and obligations apply to actors and activities in each zone. The OEI Act framework for exploiting Australia’s offshore wind resources will need to be consistent with both of these frameworks—but there are some differences between the two.

In particular, under the LOSC, the key distinction between zones is made at 12 nautical miles from the coast—which marks the end of the coastal State’s sovereignty over the territorial sea, and the beginning of the coastal State’s sovereign rights in the exclusive economic zone (‘EEZ’) beyond. But under the OCS, the critical division is at 3 nautical miles from the coast, which divides the ‘coastal waters’ (over which individual states and territories have jurisdiction) from the area of Commonwealth waters beyond.

How does the OEI Act work?

The OEI Act provides a framework to regulate the construction, installation, commissioning, operation, maintenance, and decommissioning of offshore renewable electricity infrastructure (collectively, ‘offshore infrastructure activities’) in the ‘Commonwealth offshore area’. Consistent with the OCS, this area is defined to encompass the waters, seabed and subsoil beyond 3 nautical miles from the coast, extending to the outer edge of the 200 nautical mile EEZ.

Under the Act, the Minister is empowered (following public consultation) to declare specified areas suitable for the conduct of offshore infrastructure activities. Four sorts of licences can be issued for the conduct of those activities in a declared area:

- feasibility licences (for scoping activities)

- commercial licences (for the exploitation of renewable energy)

- research and demonstration licences (to develop and test emerging technology), and

- transmission and infrastructure licences (for storing, transmitting and conveying energy).

To make the regime effective, the Act prohibits the conduct of any offshore infrastructure activities in the Commonwealth offshore area without a licence.

The OEI Act also provides two measures for the protection of offshore energy infrastructure:

- short-term ‘safety zones’, which are designed to ensure the safety of workers, vessels and structures during the construction or repair of offshore energy infrastructure,

- and longer-term ‘protection zones’, designed to prohibit or restrict vessels from conducting activities that may result in damage to offshore energy infrastructure.

The Act establishes offences in relation to the conduct of unauthorized activities in these zones—although offences in protection zones are expressed not to apply to foreign nationals and foreign vessels except in specific circumstances.

Since the OEI Act only applies to activities in the Commonwealth offshore area, the passage of undersea cables through coastal waters, and their connection to the grid via access through public or private land, will be governed by state and territory legislation.

A more detailed analysis of the OEI Act is provided in this article, and you can also visit the website of the Offshore Infrastructure Regulator (a statutory role that has been assigned, perhaps ironically, to the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority).

What are the legal issues?

The OEI Act raises a range of interesting questions for international and public lawyers—particularly with respect to how the rights and obligations in domestic and international law can best be interpreted and applied to advance Australia’s interests, and its renewable future.

One question is about the limitations of applying a uniform regulatory scheme for all ‘Commonwealth offshore areas’ beyond 3 nautical miles, rather than taking advantage of the opportunity to apply stricter regulations in the 12 nautical mile territorial sea. In the territorial sea, Australia has sovereignty and can apply and enforce laws and regulations for the safety of navigation and the protection of installations and submarine cables. But beyond 12 nautical miles, this discretion is diminished: 500-metre ‘safety zones’ can be established around installations and ‘appropriate measures’ taken to ensure the safety of the installations and of navigation. So if the OEI Act is applied uniformly beyond 3 nautical miles, Australia may be missing out on the opportunity to apply and enforce stricter regulations for the protection of offshore energy infrastructure in its territorial sea.

Another question is how the LOSC rules on safety zones will apply to wind turbines in the EEZ. While oil and gas platforms are traditionally stand-alone structures around which a 500-metre safety zone can reasonably be declared, wind turbines are commonly clustered in ‘wind farms’. The establishment of 500-metre safety zones around a whole wind farm could effectively result in the closure of large areas of the sea to other users and uses, and impact the freedom of navigation. Given the relative nascency of offshore wind farms, the practical requirements for safety zones are still unclear, and a variety of different approaches can presently be found in the laws of other countries.

Beyond safety, there are also questions of security. Noting that these installations—and the submarine cables carrying the electricity to land—will constitute ‘critical infrastructure’ supplying Australia’s energy needs, it will also be important to ensure (within the limits of international law) that they are adequately protected, particularly in light of recent incidents from the intentional sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines to the cuts to submarine cables in Europe.

But most importantly, there will be very complicated questions to consider about how to manage competing user rights at sea, as a matter of both international and domestic law. There are a diverse range of rights and interests to be taken into account in regulating Australia’s offshore areas: commercial, recreational and Indigenous fishing; shipping; marine conservation; tourism and recreational activities; native title sea claims; Indigenous cultural heritage or other underwater cultural heritage; and submarine data cables. And some of these things will be further influenced by climate-driven changes for which data is not yet available—such as the redistribution of fish stocks and rising sea levels.

The European experience of offshore wind has clearly demonstrated the importance of marine spatial planning (MSP) as a tool through which to manage the competing (and, at times, complementary) uses of ocean spaces. Twenty-two European Union member coastal States, as well as the United Kingdom, have now adopted MSP processes, and this is an approach Australia could learn from. MSP can provide a robust, transparent and inclusive framework for managing multiple uses and achieving multiple objectives in a way that could not be achieved through piecemeal consideration, siloed consultation, or project-by-project approval. In addition, a more integrated approach provides opportunities for a more coordinated and streamlined approach to the critical issue of stakeholder engagement.

Ensuring meaningful and inclusive consultation involving all stakeholders—and developing effective and equitable outcomes representing their interests and values—is likely to be the most difficult challenge of all and will require careful planning and execution. In particular, this must be done in a culturally appropriate way that embraces the knowledge and perspectives of Indigenous Australians and acknowledges that the path to a renewable future in Australia—even in respect of offshore wind—inevitably lies across Indigenous land.

What’s next?

The OEI Act is only the first step in the journey toward unlocking the potential of Australia’s offshore wind resources: the success of the overall scheme will depend on the regulations and other legislative arrangements that are currently being put in place to implement it, the consultation processes that are conducted to support the declaration of specified areas, the environmental approvals that are obtained as part of the licensing process, and the state and territory legislation that enables its connection to land.

On 5 August 2022 the Minister for Climate Change and Energy, the Hon Chris Bowen MP, brought all of these issues one step closer to reality, announcing the first six areas to be proposed for renewable energy infrastructure activities under the OEI Act. The Minister also initiated the statutorily required public consultation in relation to the first area proposed for declaration, in Bass Strait off the coast of Gippsland, which closed on 7 October 2022.

In order to declare this area as suitable for offshore renewable energy activities, the Minister must have regard to all submissions received from the public, consult with the Minister for Defence and the Minister responsible for the Navigation Act 2012 (Cth), and consider Australia’s international obligations. Public consultations on the other five areas announced by the Minister are expected to occur over the next year—so opportunities to make a submission are not over!

As the Minister said, ‘unlocking the offshore wind industry is an exciting new chapter for Australia … Many other countries have been successfully harvesting offshore wind energy for years, and now is the time for Australia to start the journey to firmly establish this reliable and significant form of renewable energy.’ It is also an exciting new chapter for Australia’s lawyers—particularly those interested in understanding how the law of the sea might need to be applied, interpreted or adapted to reflect the renewable energy future.

The author would like to thank generous colleagues for their feedback on previous drafts of this piece, and the Energy Futures Network at the University of Wollongong for their ongoing support and collaboration in respect of research activities on offshore wind.

This essay draws on the author’s previously published article ‘Winds of Change in Australian Waters : The Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021’ (2022) 7(1) Asia-Pacific Journal of Ocean Law and Policy 137-150.