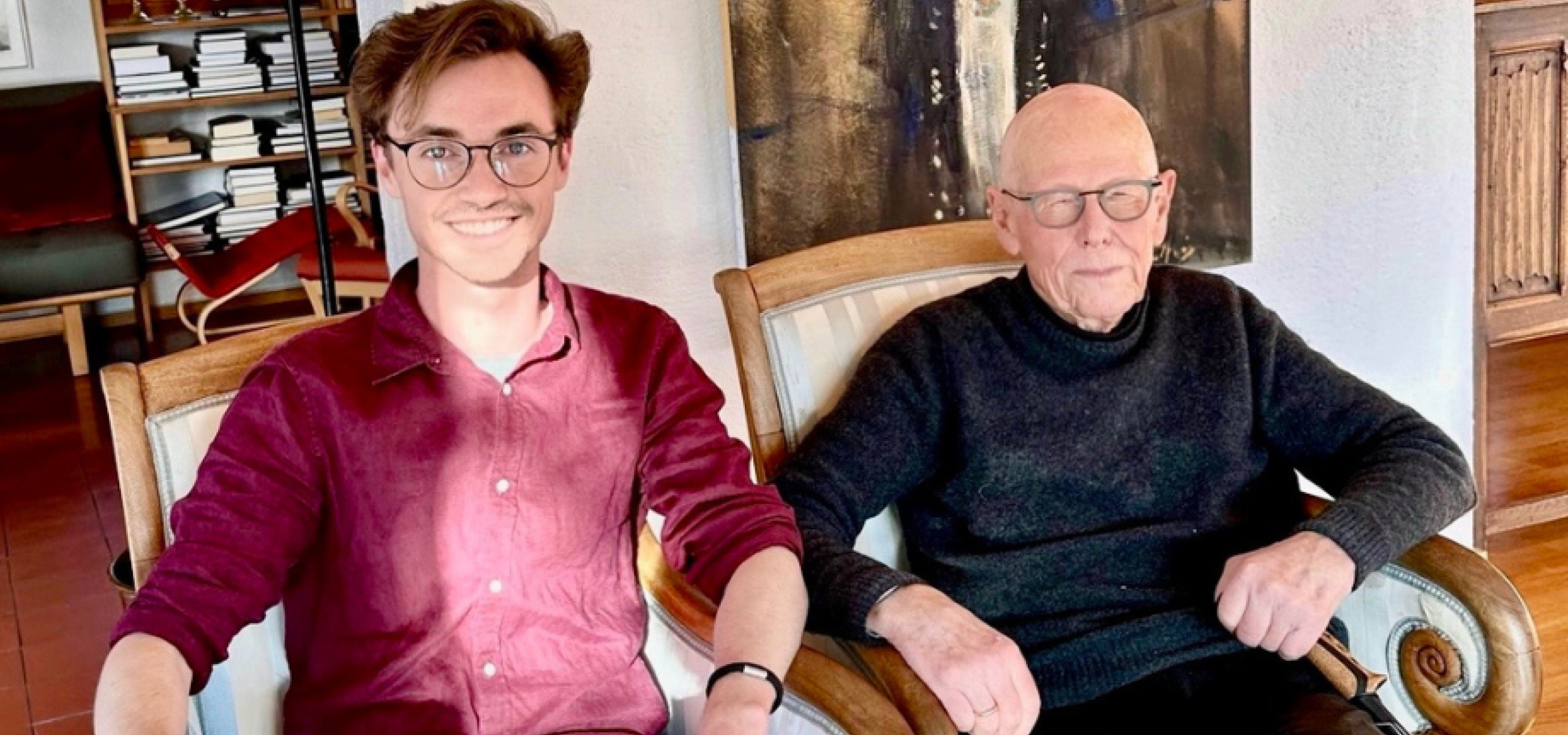

Nick Bradman, a Bachelor of Politics, Philosophy and Economics/Laws (Hons) student at ANU, with Carsten Smith, former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Norway.

In many ambiguous cases, you ultimately have to make your decision based on a holistic reasoning process that also relies on your values and life experience.

By Nick Bradman

Carsten Smith, former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Norway, is a prominent legal figure known for his commitment to social justice and human rights.

During the course of his illustrious career, Mr Smith played a significant role in advancing the rights of the indigenous Sámi people of Norway, serving as the inaugural chair of the Sámi Rights Commission.

Under his leadership, the Commission worked to promote the rights of the Sámi people and address historical injustices.

Mr Smith also undertook academic research on the topic during his time as a Professor at the University of Oslo and Dean of the Faculty of Law.

In this Q&A, Nick Bradman, a Bachelor of Politics, Philosophy and Economics/Laws (Hons) student at The Australian National University (ANU) currently on exchange at the University of Oslo, delves deeper into the life and career of Mr Smith.

Did you always want to be a lawyer—and become a judge—when you were growing up?

Law was never something I had my heart set on from a young age. When I finished school, the only thing I knew was that I wanted to go to university, but I didn’t know what I wanted to study. I took several introductory courses, and there were so many different areas that interested me. I tried taking a few in law and found it was just a natural fit for me.

But I think the other reason that I started studying law was that my father worked as a barrister. And although we never talked much about his work, I saw that it occupied much of my father’s time and often took him away on trips when I was growing up. So I think I also studied law to find out what this mysterious thing was that kept my father so busy and interested him so much. But I certainly never imagined I would end up as a judge myself.

After you finished studying law, did you enjoy your time working as an academic at the University of Oslo?

Yes. I always loved the ‘problem-solving’ aspect to law. So, getting to do academic research on different social issues—particularly in relation to Norway’s indigenous Sámi people—and help find a legal ‘solution’ was something I really enjoyed. But I also really loved getting to work as a professor and interacting with young legal minds at the university. In some ways that it still the most rewarding thing I did in my career.

What are the qualities that you think make someone a successful judge?

There are so many important characteristics that contribute to being a good judge. It is not enough to just have an understanding of the law, you also must possess a range of ordinary human qualities—including, for instance, patience, curiosity, a capacity to see things from different perspectives, and confidence to argue for what you think is right. Another very important quality is impartiality, and this only comes from being honest about your own biases or presumptions about how humans operate.

Also important is being in touch not only with the law, but also your own sense of justice. When you make rulings as a judge, particularly in Supreme Court cases, there is often ambiguity about which interpretation of the law is the ‘right’ one. And I don’t think that ‘the law’ itself can provide the solution to that problem. If it did provide a clear solution, then there would never be any disagreements between judges. So, in many ambiguous cases, you ultimately have to make your decision based on a holistic reasoning process that also relies on your values and life experience. You have to be in touch with how those things inform your sense of justice.

Australia will get a new chief justice next year. If you could give them some advice about how to do that job successfully, what would it be?

It is a difficult job, and it is a bit like overseeing a large family. I think that one of the most significant things is recognising that you won’t always be able to get all the other justices to agree with you. You can try and persuade them that your view is correct, of course, but to do the job of chief justice successfully you should also be sensitive to differences of opinion. Being comfortable with those differences is important.

I remember a book analysed the number of separate or dissenting opinions on the Norwegian Supreme Court over time and found that this number rose over my time as chief justice. But I did not necessarily see this as a negative. I also came to see these differences as a strength of the court and a valuable part of our collective reasoning process.

What were the best and worst parts about being a Supreme Court judge?

For me, the best part was having the chance to direct the future of the law in a way that you thought was just. At times, it meant you could be at the forefront of social change. The worst part was having to make decisions in cases where you thought there was no ‘good’ decision, and it was simply about making the ‘least bad’ choice. I remember that I often felt this way in several family-law cases which came to the Court.

Could you tell me about your work in the Sámi Rights Commission?

The Sámi are the indigenous inhabitants of Norway. For a long time they have suffered the effects of colonisation in Norway and elsewhere in Scandinavia—including the loss of their lands, language, and culture. The Sámi Rights Commission was one attempt to help rectify this situation. As part of my work in the Commission, we argued, firstly, for the insertion of a clause into the Norwegian Constitution which would protect their rights, and, secondly, the creation of an independent body to represent their interests (the ‘Sámi Parliament’). Thanks also to the efforts of many others, a section regarding the Sámi was inserted into the Norwegian Constitution in 1988 [then s 110a, now s 108] and the Sámi Parliament was created in 1989.

How important do you think the Sámi Parliament and s 108 of the Constitution are in advancing the position and rights of the Sámi people in Norway?

Very important. The new section on the Sámi people [article 108] explicitly states that ‘it is the responsibility of the State...to create conditions enabling the Sámi people to preserve and develop their language, culture and way of life’. This helps ensure that the position of the Sámi in Norway, as this countries Indigenous minority, can be upheld not only by political goodwill but also the rule of law.

The Sámi Parliament, meanwhile, has been very important in assisting the Sámi to express themselves in a strong and democratic way to the Norwegian government. Prior to the creation of the Sámi Parliament, non-Indigenous Norwegians could simply make assumptions about what the position of the Sámi people was on a particular issue. This could lead to policies that were inconsistent with the wishes and needs of the Sámi.

Alternatively, even if the government tried to be ‘good rules’ and ask the Sámi people what they wanted, different groups of Sámi people would often express very different views —making it unclear what the government should do. To solve these issues, I argued that the Sámi people should be helped to congregate in an official and democratic way—enabling them to present their views in a strong and relatively unified way. The elections of the Sámi Parliament have also allowed extraordinary Sámi leaders to emerge in Norway and be powerful voices for change.

Do you think that Norway’s Sámi Parliament holds lessons for Australia?

When I was in Australia in 2007, I argued that Australia, like Norway, has a historic and international responsibility to create policies affecting its Indigenous peoples in cooperation with representatives of those peoples. That is still my view. I would hope that the profound change and relative successes of the Sámi Parliament, in enabling the voices of the Sámi people to be heard more clearly in Norway, could also provide some pointers for Australia.